Why and How to Run a Design Sprint

How can companies quickly answer crucial questions about their products and services?

Google Ventures (GV) partners Jake Knapp, John Zeratsky, and Branden Kowitz set out to answer this question and came up with the design sprint - a structured process for quickly solving problems and testing new ideas. Over several years and 100+ sprints, they’ve optimized the method and captured it in Sprint.

What is a sprint?

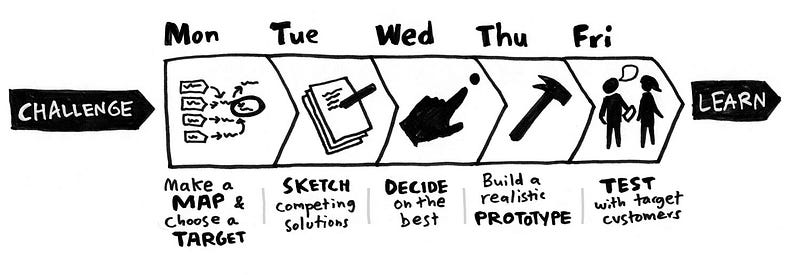

It’s a five-day process of ideating, prototyping, and testing big ideas. The anatomy of a sprint is as follows:

- Monday: Map out the problem and choose a place to focus

- Tuesday: Sketch competing solutions

- Wednesday: Make difficult decisions and turn ideas testable hypotheses

- Thursday: Build a high-fidelity prototype

- Friday: Test it with real people

Why 5 days? The GV team experimented with other time frames (2 days, a month, etc.) and found that “five days provides enough urgency to sharpen focus and cut useless debate, but enough breathing room to build and test a prototype without working to exhaustion.”

Activities are planned and time boxed, participants clear their calendar in order to be fully present, no devices are allowed, and groups are encouraged to embrace bold, risky ideas.

Why run a sprint?

Testing risky ideas quickly results in a big payoff whether they succeed (yay!) or fail (yay! Identifying a critical flaw after just a week of work is still a wonderfully efficient and informative outcome). Consider running a sprint if:

- You have a high stakes problem. A sprint is a chance to steer your company in the right direction.

- There’s not enough time. Sprints, as hinted by the name, are designed for speed.

- You’re stuck. Sprints can help teams look at problems in fresh ways.

Who should be on the sprint team?

Sprints need a multi-disciplinary team of about seven people, including a Facilitator and a Decider.

- The Facilitator keeps the sprint running smoothly. They manage time, conversations, and the overall process, and should be comfortable leading a meeting, summarizing discussions, and moving the team along.

- The Decider. The authors are unequivocal: You need a decision maker in the room. The Decider, who might be a CEO, founder, product manager, or design leader, is called upon to make tough choices throughout the week. Why not simply let group decision-making rule? Besides their expertise and vision, the Decider’s buy-in is key to the success of the outcome of a sprint. The book includes several stories to back up this point, including a chief product officer who killed off the results of a sprint (that he was not involved in) because they did not align with the company’s top priorities.

The rest of the team should have a diverse set of expertise. Consider including:

- A finance expert who can explain where money comes from and where it goes, such as a CFO or business development manager.

- A marketing expert who crafts the company’s messages, such as a marketing or public relations manager.

- A customer expert who talks to customers regularly, such as customer support or a user researcher.

- A technology or logistics expert who understands what can be built and delivered (CTO, engineer).

- A design expert who designs the company’s products or services, such as a designer or PM. The authors recommend seven or fewer group members, as they’ve found it difficult to focus and move rapidly with larger groups.

Wait, did you say something about ‘no devices’?

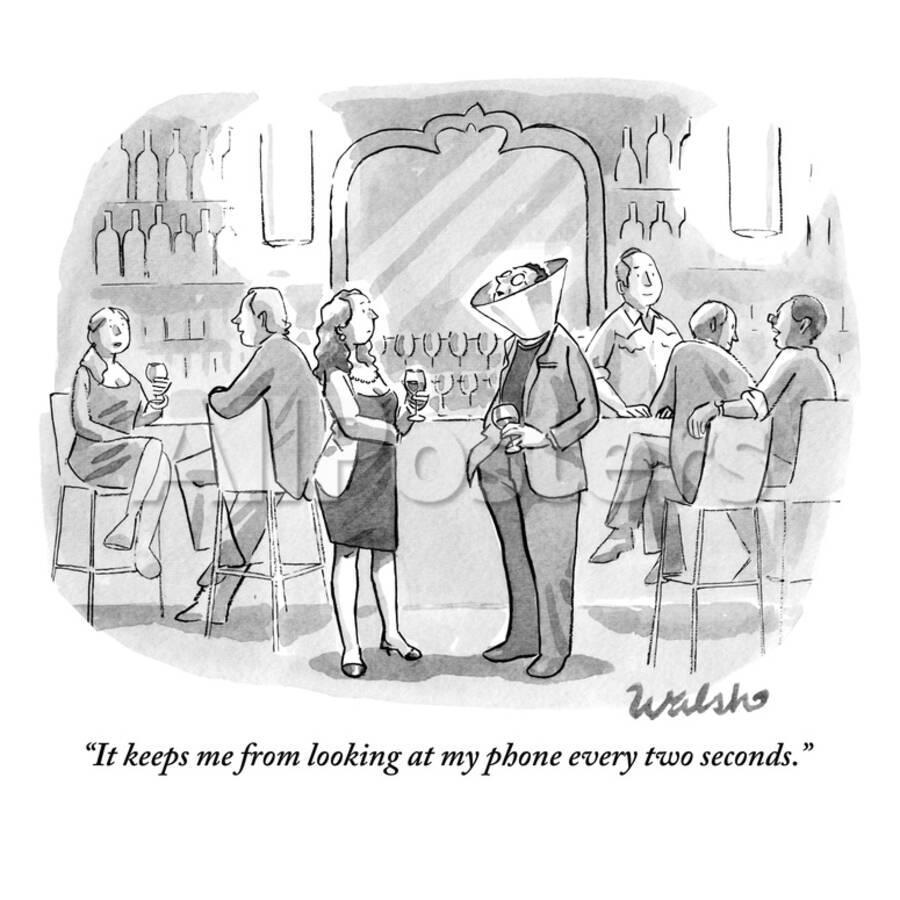

Yes. To limit distractions and keep everyone engaged, there’s no laptop, phones, or tablets use allowed.

However, if you need to use a device, you are free to step out of the room at any time (no questions asked) or wait for a break. When back in the sprint room, you should be 100% present. Sprint-related tasks, such as giving demos of existing solutions on Tuesday or prototyping on Thursday, are exceptions.

Got it. So, what do we actually do?

Let’s examine each day more closely.

Monday, Day 1: Map out the problem and choose a focus

Start slow so you can go fast.

On Monday, you’ll build the foundation for the rest of the sprint. First, agree on a long term goal by asking “Why are we doing this project? Where do we want to be six months, a year, and 5 years from now?”

Next, leverage existing knowledge. Interview experts (either sprint team members or others inside the company) share what they know and capture the problem space with a map. To create a map, start by putting your target users on the left and their end goal on the right. As experts share their knowledge, fill in the rest of the map. Meanwhile, team members should capture interview notes in the form of “How might we…” (HMW) statements.

After the expert interviews, it’s time to pick a target to focus on. Post the HMW stickies on a board and, as a group, sort them into categories. Using stickies, vote on ones you find most interesting or useful. Finally, have the Decider choose one specific target customer and one specific part of the map to focus on.

A problem map by Flatiron Health, GV-backed healthcare technology company, depicting how patients enroll in experimental drug trials. By the end of Day 1, the sprint team mapped out the basic workflow, voted on areas of interest, and decided to focus on helping coordinators match patients with drug trials.

You might notice a heavy reliance on expert knowledge, rather than customer research. It’s tough to conduct customer research in such a condensed timeline, but it’s a great idea to bring existing data into the process on Monday. In fact, GV also has a research sprint method to help you gather that data quickly.

Tuesday, Day 2: Find inspiration and sketch solutions

Great ideas don’t spontaneously appear in a stroke of genius. They are are built on top of existing solutions combined in new ways. That’s why Tuesday begins with finding inspirational ideas to remix and improve upon.

Start by having everyone come up with a short list of great solutions they’ve seen from other industries and companies, or ones that have been floating around your own company. Next, have each person give three minute demos of each solution they’ve found and captures the big idea of each one. You’ll end up with ten to twenty great pieces of inspiration.

Next, it’s time to come up with solutions using a four step sketching process.

- Take notes. Silently walk around the room and take notes to refresh your memory on the sprint goal, problem space map, and inspirational ideas.

- Generate ideas. Individually jot down rough ideas using doodles, diagrams, stick figures, or anything else that captures your thoughts.

- Crazy 8s. Take your strongest idea and sketch eight variations of it in eight minutes.

- Solution sketch. Have everyone sketch their favorite idea in a three panel storyboard. It doesn’t have to be polished, but it should be self-explanatory.

By the end of the day, everyone will have a solution sketch to share with the team on Wednesday.

Wednesday, Day 3: Decide on a direction

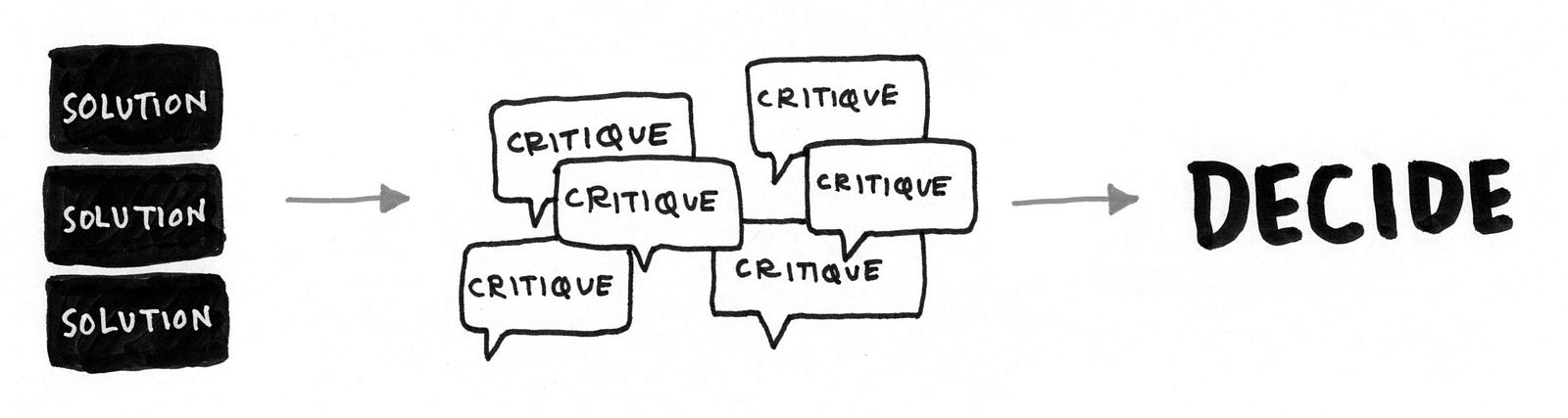

Sprint recommends the following decision-making process:

- Art museum. Post Tuesday’s solutions on the wall.

- Heat map. Have everyone silently walk around and put sticky dots on parts of solutions they find interesting.

- Speed critique. Discuss each soltion for 3 minutes. The creator is silent until the end. The facilitator should explain the sketch and capture key ideas. Then, others can bring up any concerns or critiques. Finally, the creator of the sketch can explain any missed ideas.

- Straw poll. Everyone votes on their single favorite idea.

- Supervote. The Decider gets three special votes. Whatever they choose wins, regardless of the group’s vote.

Finally, review the winning ideas and decide if they can coexist, or if you will need to build several competing prototypes to test on Friday.

Thurs, Day 4: Build a realistic prototype

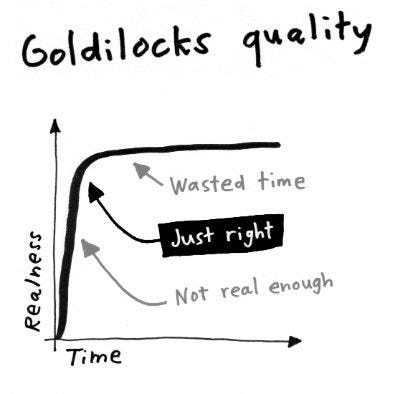

On Thursday, you will build a focused, realistic prototype of your winning idea(s) to test with users. While there are pros and cons of testing with high and low fidelity prototypes, the sprint method calls for prototypes that are realistic enough to evoke honest reactions.

The prototypes must appear real. To get trustworthy results on Friday, you can’t ask customers to use their imagination.

Remember to write an interview script for Friday’s test and do a trial run with the prototype.

Friday, Day 5: Test!

On Friday, it’s time to put your prototypes in front of real people. Throughout the week, the moderator should have recruited (or delegated someone to recruit) five representative users to come in and try out the prototype.

Set up two rooms - one for the interview and one for observation - and a video stream from one to the other. For each session: welcome the participant, ask them background questions to set context and learn more about them, and ask them to complete tasks using the prototype.

Have the team watch the sessions together. This keeps the everyone engaged and helps speed up synthesis. At the end of the day, look for patterns in what you observed, go back to your original sprint goals and questions and decide how to follow up after the week is over.

Again, whether your prototype(s) elicited negative or positive reactions, you will be far ahead of where you were on Monday. You’ll have tested a big idea and have a sense of where to go next.

Awesome! I’m considering running a design sprint, but I’m not sure I’m ready. What else can I do to prepare?

In addition to the book, there are a ton of supplementary resources online,including videos, blog posts, and a dedicated website with supplies, checklists, and even more tips on running a sprint.

And, if you’re still hesitant, just think - even reading this blog post means that you’re already more prepared than the GV team was when they started out.