Lean Customer Development - Ideas of Understanding Customers and What They Need

How does business succeed? By providing value to customers. How does business provide value to customers? The answer from Cindy Alvarez’s book Lean Customer Development: Build Products Your Customers Will Buy suggests that the key lies in lean customer development.

The book gives me important insights on how to validate product ideas through customer development research. The book demonstrates the knots of bots of understanding customers and how to deliver solutions to them.

The book is threaded by three major parts:

- Creating hypothesis (Chapter 1)

- Testing hypothesis (Chapter 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

- Build solutions (MVP) (Chapter 7, 8, 9)

What is Lean Customer Development? Why does it matter?

Essentially, customer development is geared towards understanding customers’ problems and needs and building solutions that solves customers’ problems, the precondition of business success. Lean customer development is particularly adaptable to fast-moving industries, with its focus on small-batch learning, validation, and innovation. Cindy Alvarez summarized it succinctly,

“Everything you do in customer development is centered around testing hypotheses.”

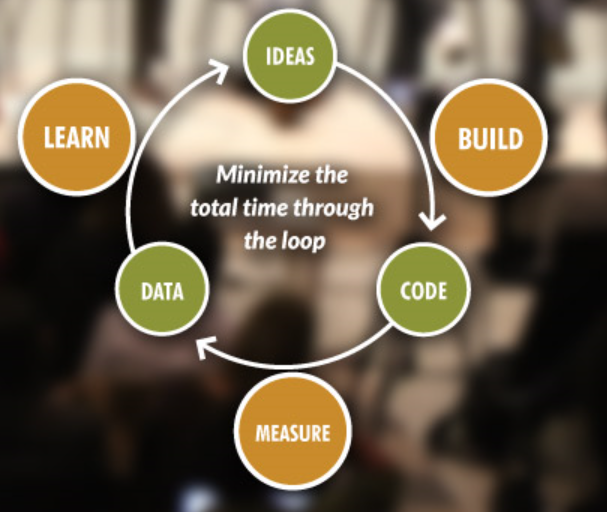

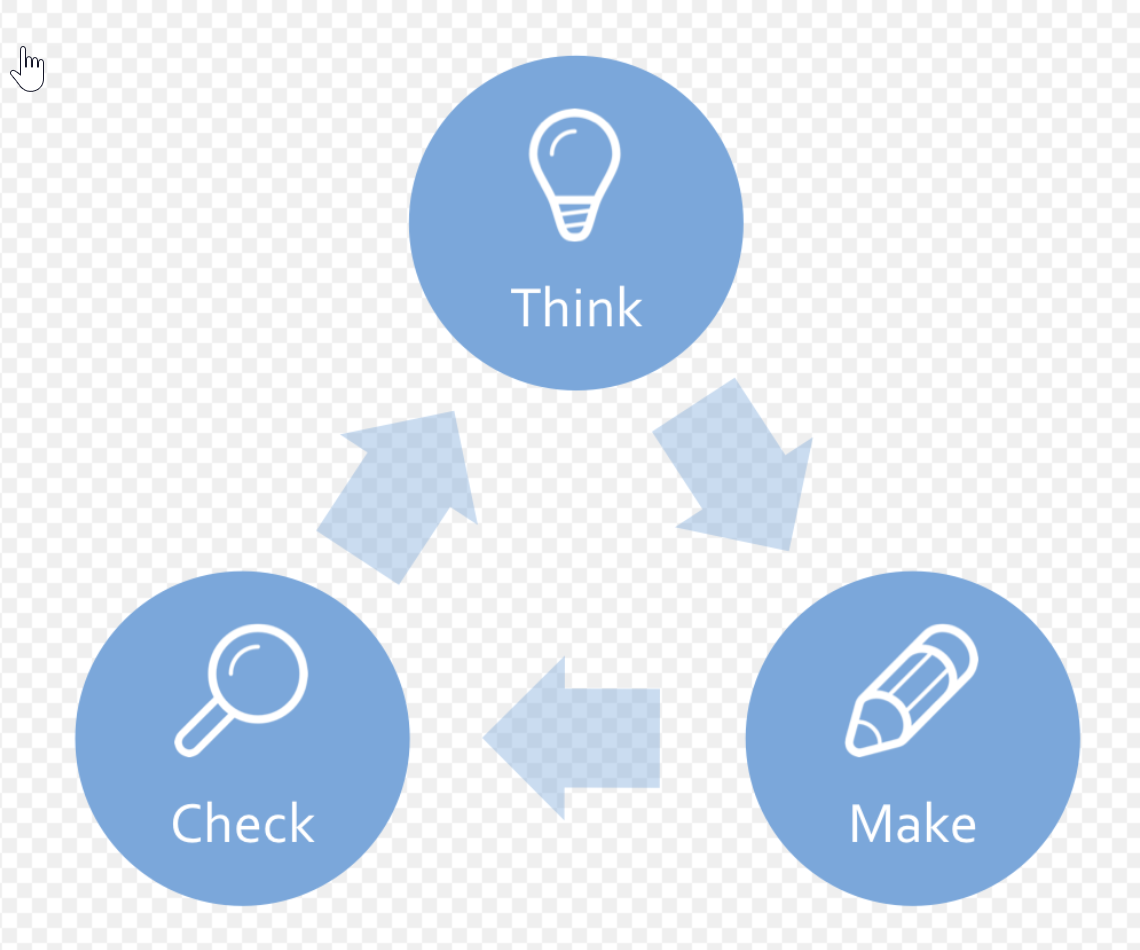

With the traditional feedback loop “Build -> Measure -> Learn”, the cost of experimenting is high because many products end up being not what users need. Customer Development focuses on the Think phase in “Think -> Make -> Check”, allowing you to explore and iterate in a rapid rhythm with low cost.

Build - Measure - Learn Feedback Loop

Build - Measure - Learn Feedback Loop

Think - Make - Check Feedback Loop

Think - Make - Check Feedback Loop

Hypotheses Validation

It all starts with hypotheses. Customer Development is a hypothesis-driven understanding of users’ pain points. Even when we already have products, we may still need to check our hypothesis. This also connects to the points made in Travis’ and Jessica’s book Customer-Driven Playbook. And hypotheses include who your customers are, what problems and needs they have, how they are currently behaving, which solutions customers will pay you for, etc,.

I believe [type of people] experience [type of problem] when doing [type of task].

Finding Customers

Finding the right people to talk to is crucial because the data collected is only valid when they are your prospective customers. The book makes an interesting distinction between “earlyvangelist” and “early adopters.”

Earlyvangelists, in Steve Blank’s term, are the most passionate prospective customers who are willing to take a risk on your unproven products. However, early adopters are people always rush to buy the latest device and pride themselves on that. They won’t help you much with validating or invalidating your hypothesis because they are willing to try just anything new! In the early phase of customer development, it’s important that you could talk to earlyvangelists.

Asking for people to commit time and attention is challenging, but it is possible because humans are all motivated by the same desires.

- We like to help others

- We like to sound smart

- We like to fix things

Interviews

This part of the book is what I found most valuable because it drills down to the specifics of how to get close to learning truth by asking effective questions. And it uses examples to illustrate how human psychology works.

In conducting interview, oftentimes researchers are tempted to ask customers what they want, but a important caveat of it is that customers often don’t know what they want. More importantly, there is an obvious tension between customer wants and needs. Do we really want to build everything that customer wants? This book is skeptical of this, and instead suggests we should build things that customers need.

For example, in my research experience working in DevDiv team, once I conducted a usability study on user’s feedback on Visual Studio interface. One user expressed that he’d like to see the interface to be as configurable as possible. Nevertheless, I knew from previous studies that this is something that frequently bubbled up but oftentimes more configuration did not increase usage accordingly.

This is perhaps one of my favorite quotes throughout the book.

“Customers may not know what they want, but they can’t hide what they need.”

On a similar note, it is tempting to ask customers to suggest features or designs, but this doesn’t mean that when we provide such features or designs, they will definitely pay and use it.

It is the UX researcher’s job to uncover those needs, which often aren’t articulated but requires researchers to push beyond surface-level answers to deep motivations, desires, and values. Three ideas related to getting the deep meaning that I found illuminating are:

- Abstract up one level – define the problem broadly so that you don’t prematurely constrain what your potential customers say.

- Getting subjective answers from objective questions.

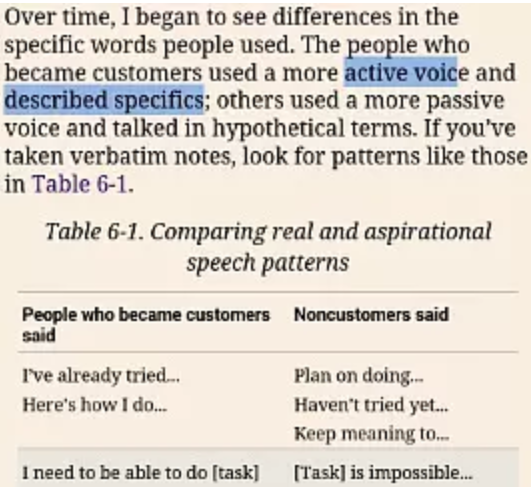

- Focus on actual versus aspirational behavior. People are likely to project a more virtuous self when they think about future behaviors.

Present versus past

Present versus past

Another common question in conducting interview in the customer development stage is, is it a good idea to show your product (or ideas of product) at this stage to get feedback? The author stresses that it’s best to hold onto showing specifics of products until the end of your conversation. The reason is that images or tangible specs will likely influence interviewees to subconsciously tailor their answers based on your product, which is perfectly summarized in this quote,

“If you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

Good insights come from valid data gathered through effective methods. Knowing what to learn, and designing good questions to probe into the right space, with the right audience, is crucial in discovering and understanding what users’ problems are, what they truly need, and what products and services can alleviate their pain points and provide value to customers.