Running Lean

One of the most common Lean/Agile software development principles that I’ve seen paraphrased is to, “value conversation over documentation”. Ash proposes, early in the book, that the “true purpose” of a business plan lies in, “…facilitating conversations with people other than yourself.”

He continually weaves this point throughout his book by emphasizing that one of the primary purposes of his one-page “Lean Canvas” template is to spark conversation.

He extolls the following three virtues of adopting a one page business model format.

Speed

They are faster to create/write compared to traditional business plans.

Conciseness

They force you to distill the essence of your product into just a few words.

Portability

The distilled essence is much easier to share it with others.

The central theme of this book is de-risking your plans through continuous experimentation.

On page 66 of Running Lean Ash shares his recipe for de-risking a business plan. He calls it, “Applying the Iteration Meta-Pattern to Risks”. The sequence for de-risking any aspect of your plan is to:

-

Understand the problem.

-

Define the solution.

-

Validate qualitatively.

-

Verify quantitatively.

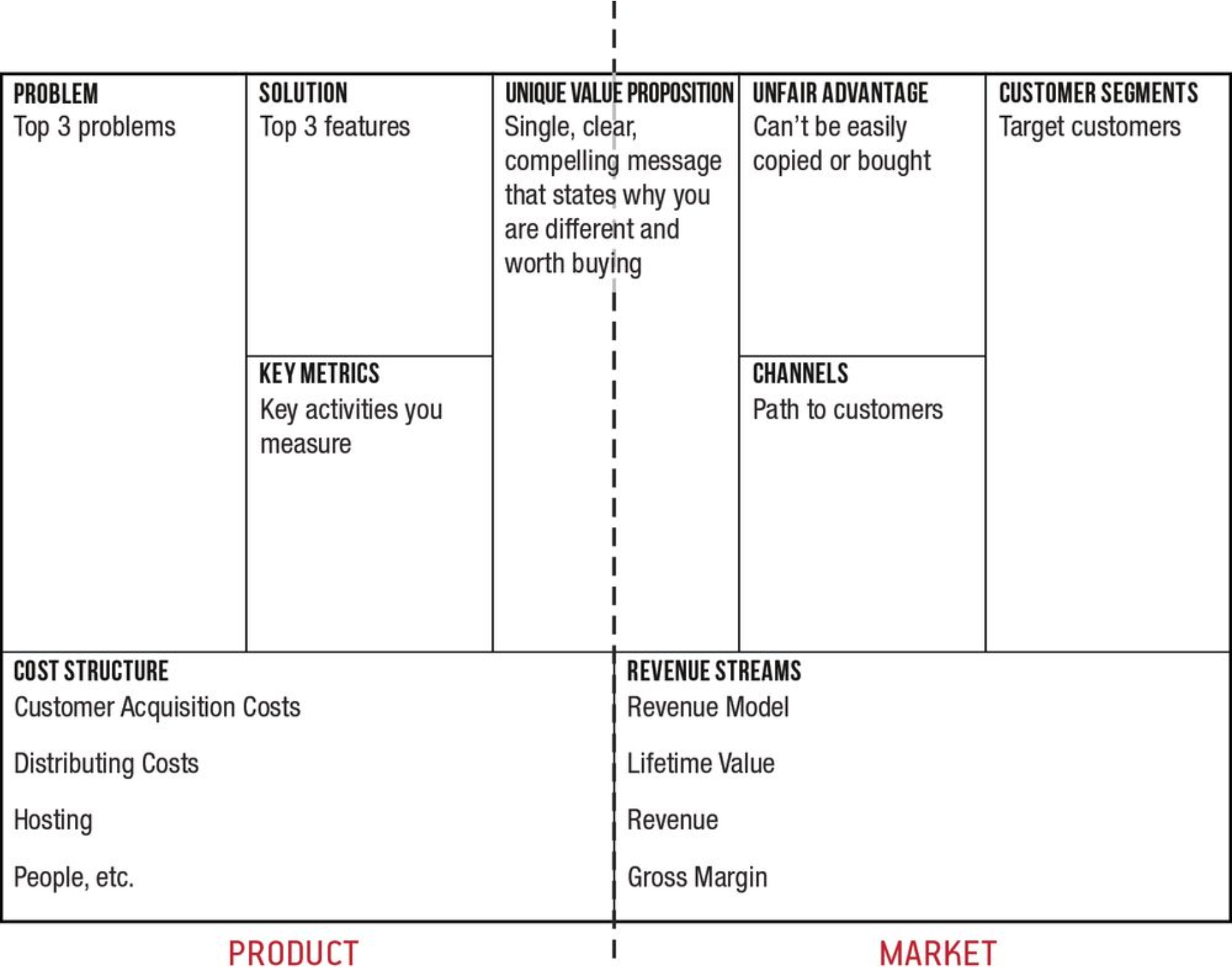

This recipe starts with capturing your assumptions relative to each of the 9-boxes in his “Lean Canvas” template. Together the boxes are designed to reduce risks corresponding to three key aspects of your plan - the product, the customer, and the market.

The Lean Canvas

The Lean Canvas

The Customer Segments and Channel boxes in his template are designed to help you capture critical assumptions that need to hold true in order for you to “build a path to customers”. The Problem, Solution, Unique Value Proposition, and Key Metrics boxes focus on capturing critical assumptions you need to test in order to ensure you are working on product that is “something people want”. Finally, the Revenue Streams and Cost Structure boxes focus on capturing assumptions you will need to test in order to ensure that you are, “building a viable business”.

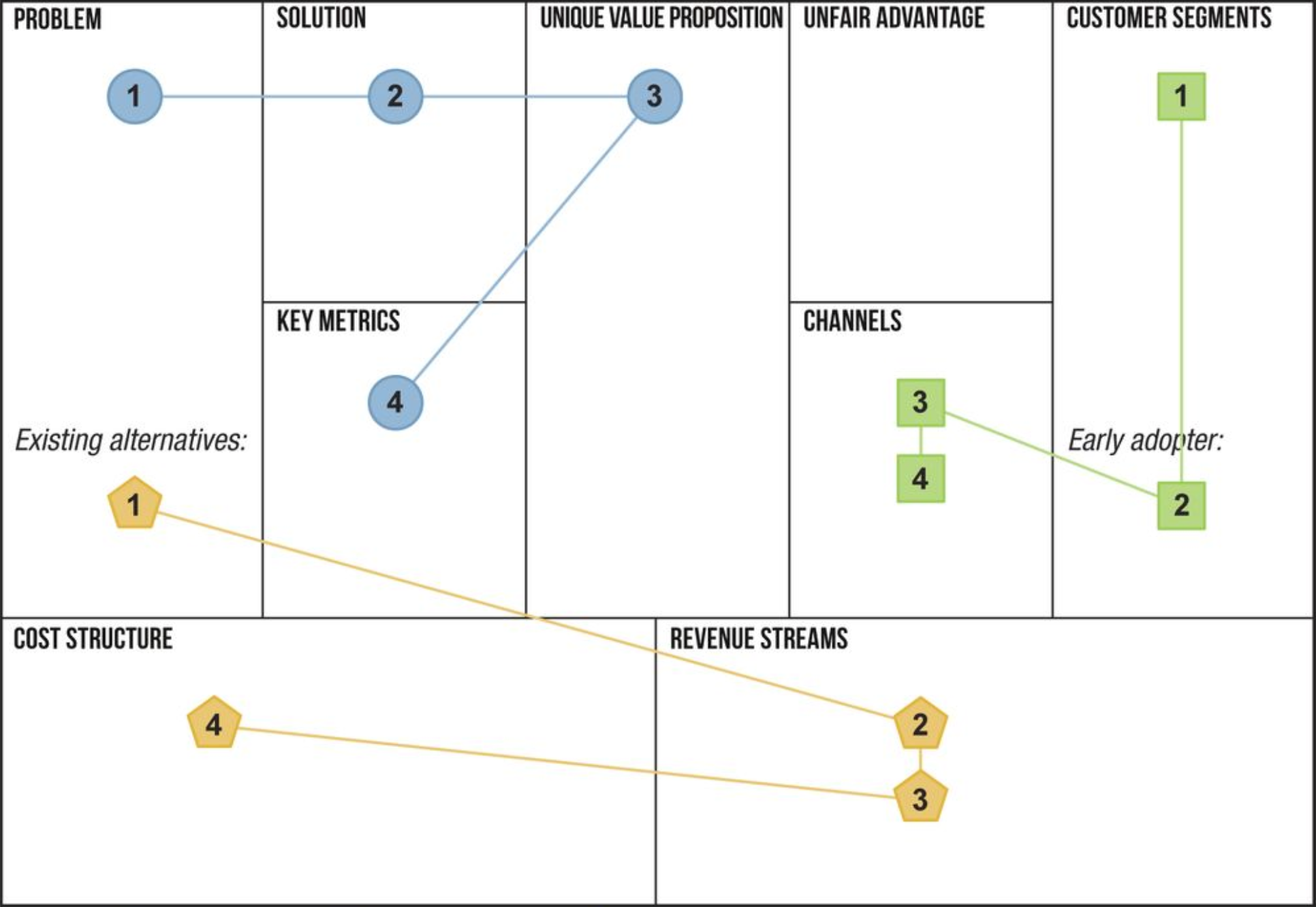

Ash goes on to prescribe a four step workflow for de-risking each of the three aspects of your plan. The four steps of each of the following mini-workflows tie back his basic iteration meta-pattern.

Product risk: Getting the right product

-

First make sure you have a problem worth solving.

-

Then define the smallest possible solution (MVP).

-

Build and validate your MVP at small scale (demonstrate UVP/Unique Value Proposition).

-

Then verify it at large scale.

Customer risk: Building a path to customers

-

First identify who has pain.

-

Then narrow this down to early adopters who really want your product now.

-

It’s OK to start with outbound channels.

-

But gradually build/develop scalable inbound channels - the earlier the better.

Market risk: Building a viable business

-

Identify competition through existing alternatives and pick a price for your solution.

-

Test pricing first by measuring what customers say (verbal commitments).

-

Then test pricing by what customers do.

-

Optimize your cost structure to make the business model work.

These mini-workflows for “Systematically Reducing Risk” are illustrated in the following diagram found on page 67 of his book.

Systematically Reduce Risk

Systematically Reduce Risk

The way that Ash consistently prescribes the same meta-pattern for Lean learning across the whole product inherently normalizes, and thereby simplifies, such broad tasks as idea generation, feature development, naming, product positioning, and business model/pricing.

The unique value proposition (UVP) concept that Ash prescribes in his Product risk workflows is the same as the “must have experience” concept described in Hacking Growth or the “core value proposition” concept described in Value Proposition Design.

“The key to unlocking what’s different about your product is deriving your UVP directly from the number-one problem you are solving. If that problem is indeed worth solving, you’re more than halfway there already.”

Ash goes on to prescribe the following 7 guidelines for Crafting an effective UVP:

-

Be different, but make sure the difference matters.

-

Target early adopters.

-

Focus on finished story benefits (i.e., benefits derived after using your product).

-

Pick your words carefully and own them.

-

Answer: what, who, and why.

-

Study other good UVPs.

-

Create a high-concept pitch (i.e., distill concept into a memorable sound bite).

Another area where Ash provides more emphasis, depth of thought, and guidance relative to other books in the Lean series is around the types of channels you can leverage to “build a path to your customers”.

He claims that, “failing to build a significant path to customers is among the top reasons why startups fail.”

One distinction he makes between channel types is between inbound and outbound channels.

“Inbound channels use ‘pull messaging’ to let customer find you organically, while outbound channels rely on ‘push messaging’ to reach customers.”

Ash points out that when first getting started you may have to rely on outbound channels to get a foothold with customers. He emphasizes the scaling benefits of mixing in or shifting to inbound channels as soon as possible.

Examples of inbound channels:

- Blogs

- SEO (search engine optimization)

- Ebooks

- White papers

- Webinars

Examples of outbound channels:

- SEM (search engine marketing)

- Print/TV ads

- Trade shows

- Cold calling

- Direct sales force

As he transitions into providing tips onto how to test your assumptions about your target customer, the problem you are trying to solve, and the viability of your business model it quickly becomes evident Ash strongly supports customer interviews as a useful experimental method.

“The fastest way to learn is to talk to customers. Not releasing code, or collecting analytics, but talking to people.”

He points out that starting your learning process with focus groups or surveys is usually a bad idea.

“Surveys assume you know the right questions to ask.

It is hard, if not impossible, to script a survey that hits all the right questions to ask, because you don’t know what those questions are. During a customer interview, you can ask for clarification and explore areas outside of your initial understanding.

Customer interviews are about exploring what you don’t know you don’t know.”

When comparing the merits of interviewing to quantitative metrics he notes.

“But more important, metrics can only tell you what actions your visitors are taking (or not); they can’t tell you why this is happening.”

In outlining the strategic role of one-on-one conversations/customer interviews Ash makes an observation that really resonated with me.

“…there is a lot more to building a great product than numbers. For starters, you have to be able to go to the people behind the numbers. …Here’s why: metrics can’t explain themselves. When you first launch a product or new feature, lots of things can and do go wrong. Metrics can help you identify where things are going wrong, but they can’t tell you why. You need to talk to people for that.”

Ash includes a list of basic tips-and-tricks for getting yourself into the right head space for having a great interview or series of interviews. He recommends the following:

-

Build a frame around learning, not pitching.

-

Don’t ask customers what they want. Measure what they do (or recall doing).

-

Stick to a script.

-

Cast a wider (recruiting) net initially.

-

Prefer face-to-face interviews.

-

Start with people you know.

-

Take someone along with you.

-

Pick a neutral location.

-

Ask for sufficient time.

-

Don’t pay prospects or provide other incentives.

-

Avoid recording the interviewees.

-

Document results immediately after the interviews.

-

Prepare yourself to interview 30 to 60 people.

-

Consider outsourcing interview scheduling (e.g., to a digital assistant).

Finally, as Ash wraps up the book he outlines one last “big idea” in which he perfectly encapsulates the future of customer-driven business processes.

“Every process works well until you add people. The key is to build a continuous learning culture of experimenters versus specialists, where it’s everyone’s job to be accountable toward creating and capturing customer value.”