Design-Driven Innovation - Applying Customer-Driven Methods to Create New Markets

One of the most common questions we get during our Customer-Driven Engineering workshops is, “How can I remain customer-centered, if there is no market yet?”

People will often refer to automotive pioneer Henry Ford’s famous quote:

“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

The root of this question is simple.

How can a team be forward-thinking or radically innovative if they are required to validate their future vision will solve a problem for customers today?

That’s the question Roberto Veraganti addresses in his book Design Driven Innovation: Changing the Rules of Competition by Radically Innovating What Things Mean.

Every Product Has Meaning

A major theme in the book is that people do not buy products, they buy meanings. This notion is quite similar to the ethos behind Clayton Christensen’s “Jobs to Be Done” framework.

Essentially, Veraganti claims that customers “buy and use products for deep reasons, often not manifest, that include both functional utility and intangible psychological satisfaction”.

“Sneakers,” Veraganti demonstrates, “are not cheaper versions of sophisticated and elegant leather shoes. Simply put, they have a different meaning.”

In this book, the word design is reserved for a broader interpretation; beyond just style and form. Design-Driven Innovation recognizes the “endorsed link between design and meanings” and looks to leverage design-thinking to drive at articulating new meanings for products.

Veraganti challenges companies to invest in radical innovation of meanings. He doesn’t believe that companies can achieve radical innovation by simply asking customers for feedback on existing products.

If a company tests a breakthrough change in meaning by relying on a typical focus group, people will search for what they already know. And they will not find it in a product that is radically innovative, unless they encounter it in the right scenario.

However, it should be noted that Veraganti is not suggesting companies remove customers from the equation. Rather, the “customer” you’re looking to collect feedback from is actually an Interpreter.

The Power of Interpreters

Apple’s popular, long-time, manifesto perfectly describes the Interpreter:

Here’s to the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the round pegs in the square holes… The ones who see things differently — they’re not fond of rules… You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them, but the only thing you can’t do is ignore them because they change things… They push the human race forward, and while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius, because the ones who are crazy enough to think that they can change the world, are the ones who do.

Steve Jobs brought the iPod to market and, not only saved Apple, but completely re-defined the meaning of music. He was able to interpret industry signals and envision the future of digital music for the everyday consumer.

Jobs understood that current solutions were just technology substitutions; they were offering the same meaning (e.g. listening to music on the go), but just replacing the technology (e.g. instead of a CD walkman, an .mp3 player). They had many of the same limitations.

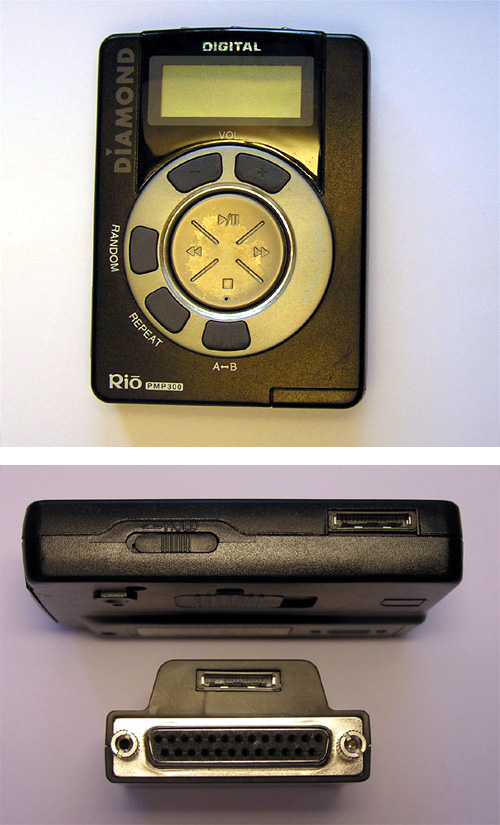

For example, the Diamond Rio PMP300 was much smaller than a CD walkman and removed the constraint of having to carry around a bunch of CDs, but it still could only hold about 30 minutes (32 MB) of music. Additionally, Diamond Multimedia left acquiring new digital music to partners like Music Match and Goodnoise. Their software was considered a means to get digital content onto the player, not central to the entire experience of listening to music.

The Diamond Rio PMP300

The Diamond Rio PMP300

Jobs had listened and observed the market and had interpreted a new meaning for digital music. He proposed an entire ecosystem that:

- Assisted customers in converting their existing music to a high-quality digital format.

- Enabled customers to purchase new digital music, legally, flexibly and inexpensively.

- Allowed for management of digital music libraries, both on the the computer and the player.

- Leveraged the latest in storage technology to allow many more songs to be stored on a single device.

When the 1st generation iPod shipped, it came in 5GB or 10GB storage options.

This was because the iPod used a hard drive that was originally designed for laptop computers. Jobs had interpreted a new meaning for this new hard drive and worked with manufacturers to enable its use with his vision for the iPod. This move allowed Jobs to claim that the iPod was the first digital music player that allowed, “a thousand songs in your pocket,” which became an important differentiator.

With the success of the iPod, Apple was able to then propose new meanings to customers on how they should manage their digital content. The MacBook, iMac, iTunes, iPhoto, iMovie, and iPod became tools that helped you manage and share your digital lifestyle. These were more than a technology substitutions, these were technology epiphanies.

Leveraging a Network of Interpreters

Veraganti isn’t proposing that companies must find a sole Interpreter to help them achieve radical innovation of meaning. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

He encourages companies to build a network of Interpreters. To seek out those that are investigating and giving meaning to the observations around them. These people will be involved in the “design discourse” and companies should look for ways to, not only participate in the discourse, but to influence those networks as well.

With the iPod, Jobs enabled Veraganti’s 3 phases of participating in the design discourse: Listening, Interpreting, and Addressing.

Listening

Accessing knowledge about possible meanings and languages of new products.

Interpreting

Generating your own vision and proposals for new meanings and languages.

Addressing

Diffusing your vision to other Interpreters.

Apple was not only listening to the discourse of digital music and mobile hardware technology, they were influencing it.

In order to drive at radical innovation, companies must discover and participate in the design discourse that influences their business strategy. They must seek key influencers and engage them before their competitors do.

Jobs, of course, was a strong interpreter who infused radical innovation as part of Apple’s operating DNA. Customers now look to Apple to define new meanings. With the introduction of smartphones, Apple was once again able to propose a new meaning with the iPhone.

Applying Customer-Driven Methods Within the Design Discourse

It is not that Lean customer-driven behaviors “fail” when trying to define new markets; it’s that they cannot be applied to your current customers.

Formulating assumptions into hypotheses and testing those hypotheses by proposing and quickly iterating on concepts are still key behaviors when developing new market opportunities.

However, companies should deploy these efforts within the design discourse. Not with their existing customers.

Companies should perform rapid experimentation with Interpreters and use customer-driven artifacts (e.g. hypotheses, discussion guides, concept value tests, sensemaking, etc.) to drive their participation within the design discourse.

Proposing new meanings within the design discourse is a great way to check your assumptions about the potential of new market opportunities. It also positions your company as a leader driving future developments, rather than a observer responding to market trends.

Veraganti gives many more examples of companies, just like Apple, that have defined completely new markets because of their ability to partner with influences, integrate themselves within the design discourse, and diffuse their vision within those communities.